The Philippines has possessed some of the world's biologically richest tropical forests. The mountainous geography of the 7,100-island archipelago has historically supported a diverse array of flora and fauna, originating from three major biogeographic regions (i.e., Formosa, Celebes, and Borneo) and characterized by high degrees of endemism (

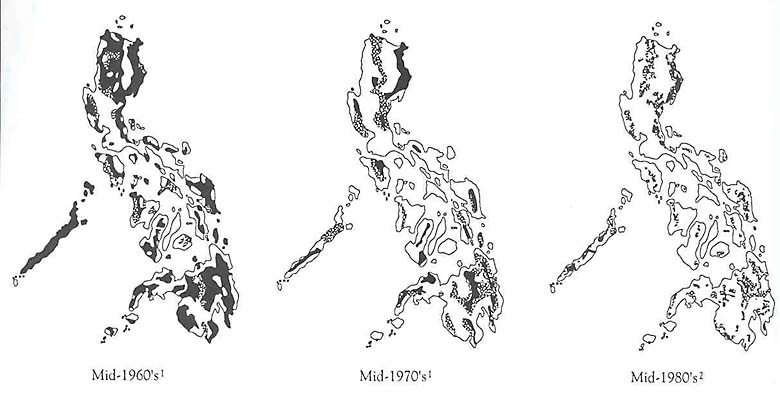

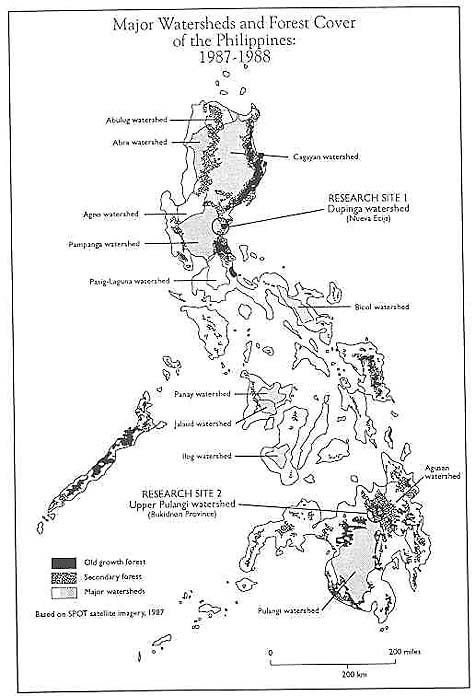

FN 1). The nation's six major tropical forest types-mangrove, molave (Vitex parviflora), mixed dipterocarp, tropical montane, pine, and mossy-have been host to an estimated 12,000 native plants, 165 species of mammals, and 570 bird species (FN 2). As recently as 1900, these forest ecosystems covered 70-80 percent of the country (FN 3). Most of this forest has been situated in the "uplands," defined today as equal to or greater than 18 percent slope.Over the past half century, as the country steadily increased its annual timber production and expanding human populations converted forests to agricultural lands, forest cover has drastically declined (see Figure 1). This trend is especially striking for the primary forests. Timber production soared during the post -- World War II period, peaking in 1975 and falling off sharply once stricter controls were established in the late 1980s. During the past few decades, many of the Philippines' forest ecosystems have experienced extensive degradation due to overexploitation by logging, burning, and agricultural clearing. Land satellite data spatially depict the compelling disappearance of forests throughout the Philippine archipelago between 1966 and 1987 (see Figure 2). By 1987, less than 22 percent of the country's land area supported forest vegetation, while undisturbed old growth forest rep- resented less than 3 percent. Of this remnant primary growth, much is mossy forest above 600 meters in elevation, characterized by few dipterocarps or other species of commercial value (see Figure 3).

Figure 1

Philippine Forest Cover and Timber Production: 1900-1990

Figure 2

Philippine Forest Cover by Decade: 1960's-1980's

Figure 3

The loss of forest cover on the upper slopes of the nation's critical watersheds has created numerous systemic problems, for both upland and lowland communities. Deforestation has undermined the livelihoods of upland communities by accelerating erosion on upper agricultural lands and reducing forest product flows. At the same time, the clearing of forests has exacerbated downstream flooding and sedimentation, resulting in the loss of fertile croplands and creating erratic water supplies and power shortages in the lowlands which affect both rural and metropolitan areas. The problems of upland degradation have also been linked to social rnarginalization and political instability (

FN 4). An exhaustive study of the history of deforestation in the Philippines suggests that rights to forest resources have been captured by loggers and their allies. The combination of elite control and corruption has facilitated the granting of primary resources to a small group of concessionaires. This has lead to the widening of income disparities and the undermining of use regulations, encouraging upland migration of the poor to release pressure from impoverished lowland areas where socio-economic reforms were not taking place (FN 5). Upland peoples, stigmatized as 'slash and burn' farmers and encroachers of public lands, have been marginalized in the process. Responding by continuous retreat, tribal communities have been the most adversely affected. At the same time, both disempowered tribal and migrant upland communities have been attractive target audiences for manipulation by communist, Islamic, and other separatist groups, placing local forest communities in even greater conflict with the state.