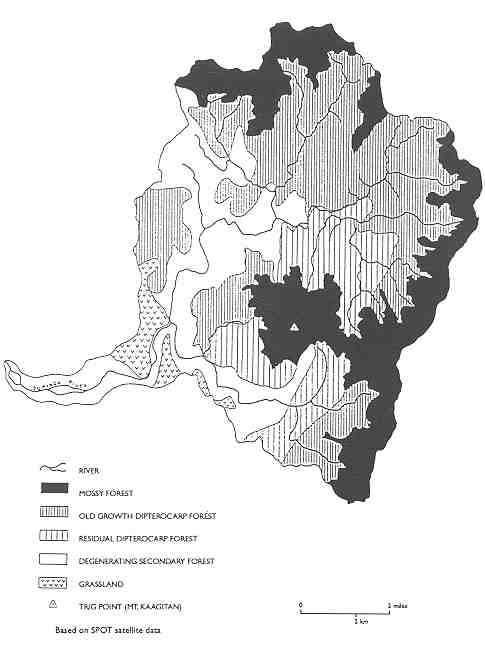

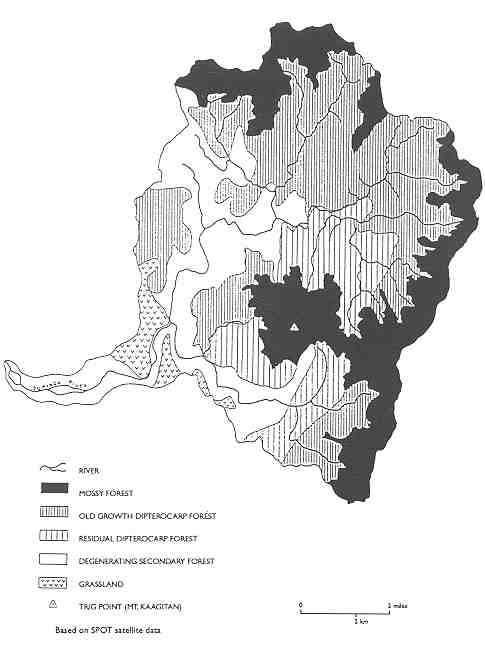

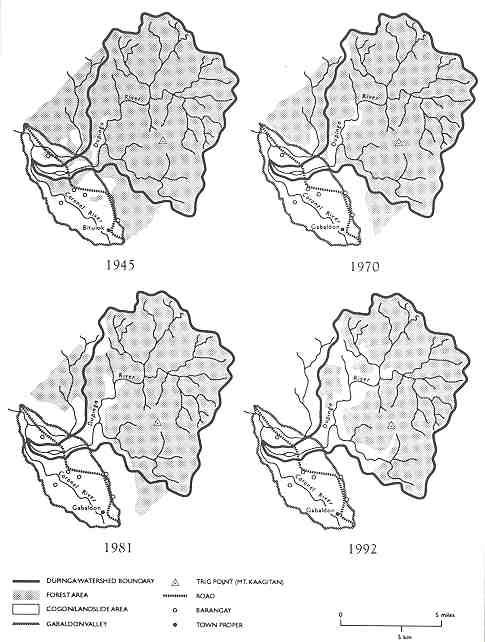

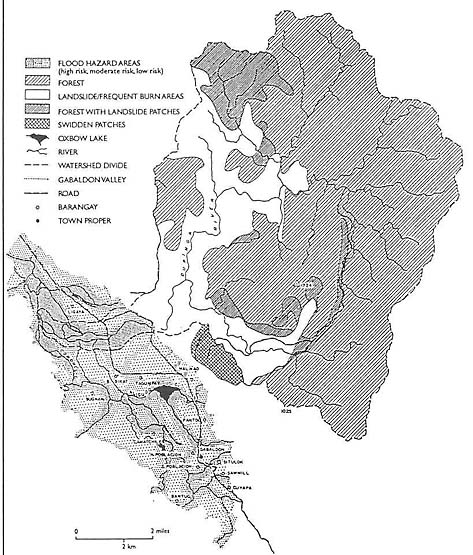

The Dupinga watershed is located in the Sierra Madre Mountains and harbors some of the best natural forest left in the Philippines (Figure 4). Located in the typhoon belt on the edge of the Pacific Ocean, these forests have been relatively protected from logging in past decades due to the violent storms that periodically lash the coast. The forest includes high-elevation mossy, as well as primary old growth and residual dipterocarp, which play multiple soil, water, and biodiversity conservation roles. The watershed spans the provincial boundaries of Aurora and Nueva Ecija. Flowing west, the Dupinga River joins the Coronel in the larger Pampanga River basin and irrigates the rich ricelands of the Central Luzon Plain. Based on its strategic location, the Pampanga has always been one of the most crucial watersheds in the country, providing water supplies to metropolitan Manila and supporting Luzon's richest primary rainforest (see Figure 5).

Figure 4

Vegetation Map of Dupinga Watershed

Figure 5

Dupinga Watershed

A review of the broader experience of the Central Luzon Plain, into which the Pampanga River drains, elucidates the problems of forest management in the Sierra Madre, and more specifically in the Dupinga watershed and neighboring communities of Cabaldon. During the nineteenth century, much of the Central Plain was converted from forest and swamp to emerge as one of the Philippines' most important rice-producing areas. Ilocano people, with a tendency to migrate, had moved into the Central Plain by the early 1800s. A century later, they were advancing into the eastern province of Nueva Ecija (

FN 22). In the early decades of the 1900s, the processes of in-migration, forest clearing, and agricultural commercialization accelerated, reaching the Coronel River valley around World War II as roads were constructed to facilitate timber extraction. This led to the progressive displacement of the Dumagats, the indigenous cultural group who had historically occupied the Sierra Madre in settlements scattered along the eastern coast and river banks (FN 23).The clearing of forests in the Luzon Plain resulted in the disappearance of small streams, lakes, and marshlands and eliminated the opportunity to cultivate crops in the dry season (

FN 24). The gradual desiccation of the lowland environment was further compounded by the expansion of logging and kaingin in the watersheds of the central Cordillera and Sierra Madre. Upland forest clearing disrupted hydrological flows and undermined natural water conservation mechanisms. The valleys became increasingly vulnerable to erosion, river and reservoir sedimentation, and more pronounced flooding and drought cycles (FN 25). Today the stabilization of the Sierra Madre watersheds has become not only imperative for forest communities in Gabaldon, but also for the Luzon rice plain and metropolitan Manila. Dwindling supplies of hydroelectric power and water flows to Manila are creating escalating problems for the city's population of over 7 million. Remarkably, logging by elite concessionaires and the military on reserves still continues in the Sierra Madre's abused upland watersheds.

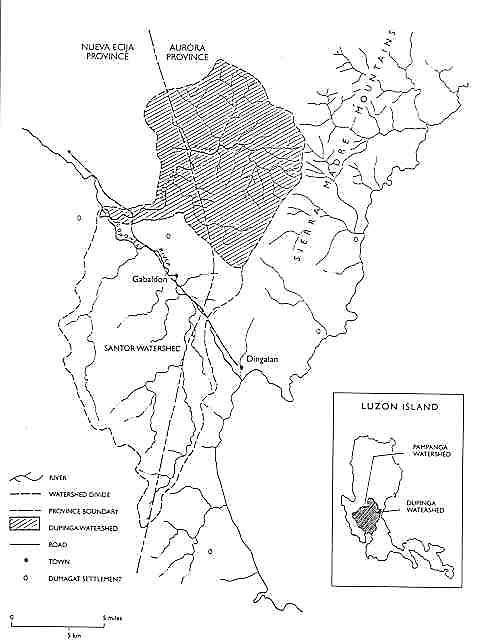

Historical forest maps of the Dupinga watershed reveal the successive opening of forests, beginning with the Coronet River basin in the 1940s and gradually moving up the Dupinga River and its tributaries from the 1970s to the present (see Figure 6). As early as the late 1800s, small Dumagat settlements were already established along the Coronet and Dupinga Rivers. As Ilocano and Tagalog migrants moved into the area, they took control and converted the riverine lands to rice fields. Dumagats moved further up the river, pushed by the migrants, eventually concentrating near the confluence of the Coronet and Dupinga Rivers. From the original scattered pattern of well-spaced Dumagat settlements along the rivers, the movements of more politically empowered lowland migrants have resulted in major settlement shifts in a series of retreats by the acquiescent Dumagats. The Dumagats' response has been to increasingly consolidate their settlements into clusters and advance further and further upriver, away from the lowlanders. Concerted attempts to organize the Dumagats in the 1980s have led to the establishment of settlements such as the one located in the foothills of the watershed above the barangay, or township, of Malinao (see Figure 7).

Figure 6

Historical Forest Maps of Dupinga Watershed

Figure 7

Lowland Migrant Movements and Dumagat Retreat in the Dupinga Watershed

The conversion of the Gabaldon valley landscape initiated the process of deforestation which has gradually progressed into the upper Dupinga watershed. Prior to World War II, most of the valley bottom was good forest or marshland, with scattered farms and settlements. Between 1942 and 1945, the Japanese occupation army constructed a road from Dingalan on the Pacific coast to Cabaldon, facilitating logging and the transport of timber from the valley to the coast. The expansion of logging activities on the lower foothills of the watershed in the early 1960s opened the area to extended kaingin. By the 1970s, the peak of logging extraction in the area, a network of roads drove deep into the Dupinga watershed, increasing the frequency of landslides and sediment loading of the river. Land pressures and poverty in the valley forced a greater number of Dumagats and landless Tagalogs into the once forested upland watershed to cultivate their swidden plots (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

Transect of Historical Land Use Pressures in Dupinga

These agricultural practices on steep slopes exacerbated erosion and increased the area subject to annual burning, in turn promoting the invasion of pioneering grasses such as cogon (Imperata cylindrica). As forest cover diminished, large areas of grass and landslides have gradually spread geographically outward from the river valleys. The primary factors fueling the transformation of the area's human ecology have been interactive: road-building into the interior and large-scale timber harvesting, lowland migrant flows, land-use pressures inducing steeper hillside swidden, illegal logging, commercialization and overharvesting of rattan, loss of agricultural lands, and natural events such as typhoons, floods, and earthquakes. Suffering the negative consequences of these cumulative processes, in the 1980s the communities of Cabaldon began organizing to protest logging and to discuss their own strategies to improve management of the watershed. A fifty-year time line of events highlights successive influences and responses to the changing human-ecological landscape of Dupinga (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

Time Line of Events Affecting Land Use in Dupinga

The case description of a Dumagat grandmother who was born and raised in the watershed also illustrates a villager's perspective on the changing influences in the area and the local resource dependencies which remain strong today (see case study below).

Dumagat Elder: History of Forest Resource DependencyRoberta, a 70-year-old mestizo-dumagat grandmother born in Lagyo on Dingalan Bay, resides in the village of Malinao, over the Sierra Madre Mountains at the foot of the Dupiga watershed. Her ancestors likely lived for centuries along the eastern coast of Luzon, moving into the forests to gather, hunt, and farm. Before World War II, Roberta's family migrated to the Dupinga area, where her father gathered rattan daily from the forest. After marrying a lowland Tagalog who was also a rattan-gatherer, Roberta herself began collecting rattan as a primary occupation. While gathering rattan, Roberta also collected other non-timber foods -- fruits such as palawai, bolete, and citrus katmun, and betel nuts. When she was younger, Roberta combined rattan extraction with hunting and fishing. She hunted deer and wild boar with a pack of ten dogs, a spear, and a bolo knife, often entering the forest alone with the dogs and killing up to four boar per week. With hand-made goggles and a notched spear, Roberta would dive for fish and eel which ran abundant in the Dupinga River. As a secondary occupation, her family practiced small-scale swidden farming, burning and planting upland patches with rice and string beans. When the Japanese entered the region in 1941, Roberta's family moved back to Lagyo. They returned several years after the war, and Roberta remembers that Dupinga looked very different. The big trees were gone, and the upland forests had receded. "Everybody was now going to the forest for their livelihood," she recalls, including many more Tagalogs who had migrated to Dupinga and begun collecting rattan. While her perception of the forest's fate infers logging operations by the Japanese, Roberta also described kaingin by Dumagats and Talalogs as a major source of forest destruction. Roberta's family became increasingly dependent on rattan extraction as the better land was progressively claimed by the Tagalogs. Eventually, her family no longer practiced kaingin. She and her relatives worked as full-time rattan collectors, selling their unprocessed rattan to the middleman who controlled prices and markets. Rattan extraction regulations were overlooked by government field foresters, who were bribed to allow open access and free collection, even in sites that were clearly suffering overexploitation. Roberta and her family extracted the maximum quantities possible, limited only by their ability to walk far distances into the forest and haul and float the rattan downriver. Roberta recalls that the Dumagats were aware of the diminishing availability of rattan stock, yet their dependency on the trade left them no option but to continue to harvest aggressively. Today Roberta notes significant changes in the environment around her village. She is convinced that the river has less water and seems weaker, except in the flood season, and that the fish are declining due to the introduction of car batteries to electrocute them. Roberta fears that given expanding demand for rattan, dwindling supplies, and current rates of extraction, the stock will be completely exhausted in a decade, when her grandchildren will be old enough to collect. She has been advising her children, who are collectors, to obtain title to a piece of land, believing that this strategy will provide a more stable economic future than depending on a declining forest resource base. |

The steady degradation of the Dupinga watershed results from a combination of both natural and human-induced activities. Among natural influences, major tectonic plates and fault lines cut through the region, activating tremors which periodically result in mass movements and landslides. The entire Dupinga, and the Sierra Madre in general, are naturally unstable, in part due to these tremors that dislodge surface and subsoils. These processes are compounded by a very steep slope distribution. The western portion of the watershed shows massive landslips. Landslides are also found in the heavily forested area of the watershed, another indication of Dupinga's natural instability.

The watershed also lies in the eastern Luzon typhoon belt, subjecting it to severe storms from the Pacific Ocean. During periods of high rainfall, rapid runoff stimulates landslides, especially in logged-over and other denuded areas. Heavy soil erosion results in the sedimentation of riverbeds, while the confluence of rapid runoff from different rivers and tributaries induces lowland flooding. As the watershed has experienced increasing deforestation, the narrow riverbeds have expanded into broad flood plains in recent decades (see Figure 10). During the extended dry season, burning of kaingin patches frequently runs out of control, suppressing natural regeneration over large areas of degraded forest lands. Since natural geophysical forces can cause unstable geomorphological and hydrological conditions, any human disturbances are prone to magnify the degree of erosion, sedimentation, and flooding.

Figure 10

Bio-Physical Influences on the Dupinga Watershed and Gabaldon Valley

Human activities which contribute to the deterioration of the watershed are distinguished between those interventions from outside the area, usually with heavy capital investments (e.g., logging, mining, and road-building), and those resulting from activities of the local population (e.g., kaingin, small-scale harvesting). Despite the fragility of the Dupinga and its severe erosion potential and downstream flooding problems, the Inter-Pacific Forest Resources Company still controls logging rights to over one-half the watershed. Although not currently operating in the area, the concessionaire's prior road construction and extraction of giant dipterocarps have increased the instability of many slopes and damaged river banks when logs were floated out.

Taking advantage of the road network, local entrepreneurs have increased small-scale illegal logging operations in the last decade. In the late 1980s, it was estimated that eleven unlicensed saw mills were operating in the Gabaldon area. Predominantly small-to-medium logs (up to 30 cm. diameter) are hauled out by buffalo along the drag trails and roads. Compared to large-scale commercial operations, these activities have less negative impact on the forest since extracted volumes are small and cause less soil compaction and erosion. Nonetheless, because small-scale loggers operate at the margins of the forest, they contribute to the gradual recession of forest boundaries. The practices of burning the undergrowth in the dry season for easy access and dragging out cut round logs are commonly visible at the periphery and strips of residual forest along the Dupinga River and its tributaries. Annual burning destroys many types of regenerating species, from small embedded seeds to young seedlings and saplings, and leads to soil nutrient depletion, elimination of soil microbes, and the collapse of soil structure. In turn, this leads to further susceptibility to erosion and landslides.

In addition to the small-scale logging, over the past twenty years a number of small-scale, open-pit mining and tunneling operations have been initiated in Dupinga. The activities have primarily involved the extraction of manganese ore in the Madulag and Agud areas (Mt. Calantas). The mining has resulted in massive soil erosion, particularly in the Madulag area, where stream measurements below the mine reflect substantially higher volumes of sedimentation than other streams in Dupinga.

The adverse impacts of logging and mining in Dupinga arise in part from the construction of roads that cut through the steep and highly sheared slopes. Using bulldozers and heavy earth-moving equipment, logging and mining operations have built a network of dirt tracts within Dupinga. Despite governmental guidelines, no reclamation has been done, nor has there been any effective monitoring or oversight of these operations. In recent years, although commercial logging operations have been suspended, small-scale timber extractors continue to use the routes in the dry season.

In addition to logging, mining, and road construction, dry season grass fires are a major force behind the transformation of vegetative cover in the Dupinga watershed. Fires are typically started by kaingeros to either clear a plot or burn older cogon, which promotes a new flush of even-aged grass that can be harvested for roofing. Many of the lower slopes of the watershed are burned consecutively each year, suppressing the regeneration of pioneering forest species. Since farmers do not tend to clear fire breaks around their plots, the fires escape upwind to larger grassy areas and neighboring forest. Both natural forests and state-sponsored efforts at reforestation along the foothills in Dupinga have suffered greatly due to fire.

While most of the burning currently occurs in the foothills of the watershed, where communities open plots for agriculture and thatch grass collection, fires also erupt in the interior of the watershed when rattan collectors clear small patches for taro cultivation or attempt to eliminate brush to improve access to forest products. As a consequence, fires are one of the most important forces in the degeneration of forest lands and the suppression of their ability to naturally regenerate. The ecological outcome is a successional stage of fire disclimax, in which the vegetative community is dominated by cogon and biologically impoverished. Research trials with natural regeneration from Cebu indicate that even in very degraded sites, forest succession processes can progress rapidly if annual burning is controlled. A low cost and effective method being tested to reduce fire spread involves lodging down the cogon grass with a board. The pressed grass allows light to reach the young tree seedlings, and when fire does occur, slows the rate and intensity of the burn (

FN 26).

The communities residing at the foot of the Dupinga watershed are troubled about their future. Landed Ilocano and Tagalog farmers fear that their rice, cane fields, and property will be washed away by torrential floodwaters rushing off the deforested uplands. Dumagat and Tagalog swidden cultivators in the foothills are aware that the expansion of cogon grasslands and the erosion of topsoils from the steep slopes they cultivate threaten productivity and their existence. Finally, the families that still survive directly from hunting, fishing, and harvesting forest rattan are acutely aware of growing scarcities. Certain lowland communities have recently begun to organize for change. They have attempted to close logging roads in Gabaldon to prevent timber exports from the area. Local communities are also worried that legal TLA holders may try to reinitiate logging operations. These community groups require the unequivocal support of the DENR to ensure that existing TLAs are permanently revoked.

Some of the farmers in the foothills of the Dupinga have begun planting mango and other fruit trees. This appears to be a carefully selected longer-term strategy to stabilize agricultural land use and realize higher profits (see case study below). Plantations of high-value fruit trees also provide strong incentives to control fire and closely manage and monitor the land.

Boyet's Experiment with Upland AgroforestryTen years ago, Boyet and his Tagalog family collected rattan from the hill forests above Malinao. As supplies diminished and the work became more arduous, Boyet shifted into tenant farming in the valley. Although landless, he preferred farming over rattan collection because it provided him with greater financial security. In 1989, the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) offered Boyet the opportunity to farm a degraded and unused upland ridge tract above Malinao. Although allegedly under DAR's jurisdiction, based on its slopes of over 18 percent, the land is also classified as public forest land, placing it under overlapping DENR authority. According to Boyet, the tenure arrangement with DAR is based on a "good faith" verbal agreement by which he will receive land title in the future -- once the land is under his longer-term cultivation. Boyet feels grateful for the opportunity to farm his "own" land and believes that the productivity potential of the area is good, despite steep slopes and a twenty-five-year cyclical history of cogon burning. With heavy inputs of labor, Boyet and his fellow workers have progressively plowed up patches of tenacious cogon to plant a combination of taro and fruit trees. With limited capital and no extension assistance, Boyet's land-use strategy has been based on a desire to cultivate high-value produce which can be channeled to the larger markets of Cabanatuan and Manila. In the lower fields, which he established first, Boyet has recently transplanted mango trees amid the taro. He chose mangos because the saplings were cheap and available in the valley and could offer potentially high economic returns. Boyet predicts that without the trees, heavy rains on the slopes will deplete soil nutrients to the point where taro cultivation will no longer be possible after three years. His hope is that by that time, the mangos will provide enough green manure and soil stability to enable extended taro cultivation and eventually to dominate the site as an orchard. Boyet no longer collects any forest products, devoting his time to his farm. He feels convinced that the partly forested ridge above his farm plot is crucial to protecting his fields from mass soil erosion and washouts. |

An estimated 255 people in the towns and villages of the Gabaldon valley, including most Dumagats, are directly dependent upon rattan collection as a major portion of their income. While settled in a community on the edge of Malinao, much of the Dumagats' time is spent in camps or semi-permanent settlements deep in the Dupinga watershed. Arguably, it is these primary forest users who have the greatest incentive to ensure that the forest resources are regenerated, enriched, and managed sustainably.

Currently, all the rattan gathered in Dupinga is derived from natural sources. Discussions with gatherers indicate that the availability of rattan has dramatically declined in those areas of the watershed near the valley communities, and that collectors are now walking long distances to extreme comers of the Dupinga catchment. While migration of rattan collection groups has been occurring into the upper watershed since the 1940s, out-migration from strategic collection points has become a more recent phenomenon since the late 1960s (see Figure 11a). Population flows are correlated to the increasing exhaustion of forest rattan; today, due to tapped out supplies, seven out of a total twelve historical supply routes are no longer utilized by collectors (see Figure 11b). While cutting the rattan canes for sale, collectors frequently gather the edible shoots as well, thereby removing new regenerating stock. Collectors estimate that commercial stocking levels will be exhausted within the next three to ten years-unless harvesting and management practices change. This reduction and increasing scarcity of supplies also elicits tension between the Dumagat and Tagalog collectors. A number of collection sites are viewed as informally exclusive to particular groups, but incursions by others continue to create conflict.

Figure 11a

Figure 11b

Some Dumagat collectors have recently expressed an interest in culturing rattan in various parts of the watershed where the environment is suitably moist and cool. Lucio, a recognized Dumagat leader, suggests Bungahan as a possible site because the remnant primary forest has large canopy trees which still provide the shade that rattan prefers. He feels that both Kapihan and eventually Soloyan are also strategic spots where rattan could be enrichment planted. Dumagat collectors estimate that it would require up to ten years for fast-growing rattan to reach an optimal 3 centimeters in diameter, although many collectors are harvesting earlier, at 1.5-1.8 centimeters. Collectors would prefer to experiment with fast-growing species such as palasan (Calamus merrillii Becc.) and alimuran (Calamus ornatus, var. Philippines Becc.). They note, however, that for a system to be successful, all collectors would have to agree to protect these areas and a consensus would need to be reached on exploitation rights and harvesting schedules. Lucio believes that the best way to manage cultured rattan in the forest is to organize two or three smaller management groups, comprised of households of user groups who wish to cooperate in the venture. He feels that individual families alone could not be caretakers of forest plantings.

Often in consort with rattan collection, hunting has been an important source of protein for Dumagat families, as well as a supplement to their cash income. Deer and wild boar are the most significant types of game, but their populations have diminished under growing pressures from both Dumagat and Tagalog hunters (see case study bellow).

Arnold: Dumagat Hunter-Gatherer and Potential Forest ManagerArnold lives in the forest most of the year. During the dry season, he walks a full two days upstream from the valley to Balawine, where he collects rattan. In March 1993, he was able to collect 21 bundles (palako) in one month (each palako contains approximately 24 canes 12-18 meters in length), floating the canes down the Dupinga River on an inner tube. Upon reaching the Dupinga bridge, he cuts the cane into 3-meter-long poles (palas), which are sold for 2 pesos (P) each. Arnold can earn up to P4,000 ($160) in two weeks on an intensive rattan collecting trip, although most collectors make much less than this in a month due to shrinking stocks. During the rainy season, Arnold camps at Lingod creek, a tributay feeding into the Dupinga River not far from the Gabaldon valley. He cultivates a few kaingin patches and hunts in the surrounding forest. A skilled hunter, Arnold still catches a steady supply of game. In early 1993 he was able to trap 10 deer using snares; he captured one alive to sell for P2,000 ($73) in the provincial capital of Cabanatuan (deer meat typically sells for one-eight as much, or P250 per kilogram). Thoroughly familiar with and knowledgeable about the area's forest resources, Arnold's continued success in hunting and rattan collection hangs in jeopardy. He notes that an increase in the number of hunters, lack of any controls, and a dwindling supply of game and rattan are making his livelihood increasingly more difficult. If given the right opportunity and support, it may be that Arnold and others like him could play the urgent role of forest protectors and managers, allowing the forest a chance to recuperate and regain its functions and full productivity. |

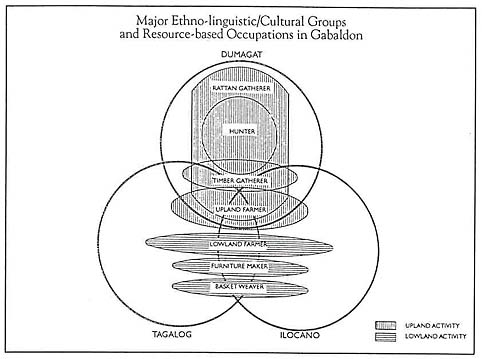

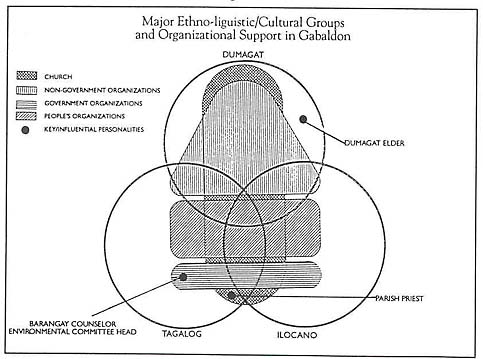

The stabilization of Dupinga depends upon the emergence of an institutional structure and accompanying social arrangements that effectively control access to the upper forests. For any land-use management organization to be effective, it requires the support of socio-political groups within the area, including the local government. Comprised of Dumagats, Tagalogs, and Ilocanos, the communities of the Cabaldon valley engage in economic activities which can be broadly categorized into those directly or indirectly dependent on the forest resources of the watershed (see Figure 12a). Due to their continued involvement with rattan gathering and hunting, the Dumagat community has the highest forest dependency and greatest knowledge of the internal ecological and biophysical conditions of the watershed. A much smaller proportion of Tagalog and Ilocano families is directly involved in forest product gathering, while many lowland farmers are indirectly dependent on upland forests for water or raw materials for cottage industries. While the Dumagats originally settled the area, they are now the most disadvantaged minority population, economically and politically marginalized compared to the Ilocano migrant landowners and merchants. Those families involved in upland occupations in Gabaldon generally earn lower incomes than households engaged in lowland activities. Moreover, the political power and distribution of services by local government and NGOs is concentrated in the lowlands (see Figure 12b). Increasing social tensions in Dupinga may be a reflection of growing resource-use conflicts. However, conflict also presents opportunities to affect change through achieving better communication, understanding, and consensus among different user groups.

Figure 12a

Figure 12b

Over the last few decades, farmers and forest gatherers living in the Dupinga watershed valley have become highly aware of the impact of upstream logging and mining on downstream flooding. Hundreds of hectares of rich agricultural land have been destroyed. Villagers have witnessed first-hand the depletion of forest resources through over-exploitation. The provincial logging ban of 1978 did little to slow the rate of destruction. In 1986, a small group of community members encouraged by the local parish priest took a more direct approach. By barricading the road, they were able to block the movement of logging trucks through the valley. The priest appealed to the Environmental Research Division (ERD) of the Manila Observatory to assist the communities with longer-term diagnostic studies to explore more sustainable ways to manage the fragile watershed.

A combination of detailed studies, community meetings, participant field observations, and consistent interactions has brought into sharper focus many of the watershed's human and resource management conflicts. ERD regarded the context as well intentioned on both community and government sides but hindered by poor mutual understanding. Early activities involved the identification of conflict situations and social instabilities through interdisciplinary analysis and evaluation. The diagnostic findings are summarized in a web chart illustrating the community's interaction with its environment (see Figure 13). Still, progress in resolving user group disputes has been slow and other events have intervened. An earthquake in 1990 caused massive landslips at many junctures in the watershed, further compounding downstream flooding. The resurgence of illegal logging later that year forced the community to once again barricade the logging road and send off a protest delegation to the DENR in Manila. While certain government officials have been sympathetic to the environmental problems confronting Dupinga communities, DENR has refused to revoke mining and timber concessions in the area. The development of a community-based watershed management agreement in Dupinga demands full participation and multi-path communication among the various sectors in the community. A series of events, community responses, and ERD interventions based on its general strategic approaches have been identified in the process (see Figure 14). Initially, social stability and reconciliation among the groups in conflict may best be achieved through a mediating "third" party-in this case an NGO. In the effort to achieve widespread multi-sectoral participation and consensus, five organizational stages have been documented by ERD (see Figure 15).

Figure 13

Web Chart of Community Issues

Figure 14

An Evolving Strategy towards a Participatory Management Agreement

Figure 15

Process for Multi-sectoral Participation in Developing a Watershed Management Strategy

Early on, while coordinating with local DENR representatives (CENRO), ERD facilitated the selection of the third party mediator through discussions with both the local government council (Sanggunian Bayan, or SB), and the church-based organization directly involved in creating greater environmental awareness (Bantay Kalikasan para sa Kinabukasan ng Kabataan, or BKKK). The responsibilities of the mediator, defined by the SB and the BKKK, are threefold: 1) establish links and develop trust and rapport among sectors; 2) conduct a series of multi-sectoral meetings; and 3) organize activities such as exposure trips into the watershed to enhance understanding of the issues. The cultivation of trust among all groups is the overriding objective of the third party mediator. After each multi-sectoral meeting, the mediator processes the data on various sectors' perceptions of specific watershed activities (mining, logging, kaingin, rattan gathering, and hunting) as a basis for developing strategies together with ERD for future multisectoral meetings.

During the first two stages, the meetings are attended by community leaders and representatives of key local government and village institutions. By the third stage, representatives from different resource user groups begin attending negotiations, with the mediator assisting them in resolving conflicts. During the fourth stage, the mediator opens the dialogue among resource users, government representatives, and the community advocacy organizations in an attempt to frame the management plan and reach a consensus among all participating groups. At present, discussants in this process are reviewing numerous proposals, including revocation of all mining and logging (TLA) leases, control of fires by establishing guidelines on firebreaks, establishment of fines and a systematic monitoring system, enrichment planting of valuable rattan species, and empowerment of Dumagat youth to act as forest patrols. During this phase, the third party becomes the primary coordinator and facilitator, while ERD simply observes the meetings. Continuous liaison with CENRO is essential in facilitating government support for the community's future resource management plans. During the fifth and final stage, a group of representatives from the primary resource users begins operationally managing the watershed, relying on other community organizations and CENRO for consultation, coordination, and technical advice. For field operations, the Dumagats, who are most closely linked to the forest, are seen as playing a principal role as stewards.

In conclusion, there is growing concern among Dupinga's lowland farmers over the erosion of their fertile agricultural lands and the flooding of their crops, while upland forest gatherers and cultivators are encountering a rapidly degenerating resource base. Their shared sentiments have provided a basis for developing a strong community coalition for improving the management of the watershed. Ultimately, building the institutional and operational capacity of a watershed management organization depends on creating a clear understanding of upstream-dowstream linkages and resource problems, resolving conflicts, reaching a consensus regarding access controls, and establishing regulatory mechanisms to ensure sustainable use practices. By identifying management opportunities, user groups can play specific roles in developing land-use plans that improve interactions between upland and downstream communities and ensure the integrity of the watershed as a system (see Figure 16).

Figure 16

|

Land use |

River water supply |

Settlement, rice and onion fields |

Cogon grass |

Degraded secondary forest, bamboo, Cogon grass |

Kaingin plot, temporary huts |

Secondary forest |

Primary forest |

|

Management problems |

Bed sedimentation, flooding; loss of agricultural land |

Inequitable land distribution |

Frequent fires, soil erosion, low productivity, suppression of secondary succession |

Fires, soil erosion, suppression of natural forest regeneration, rapid water runoff |

Soil erosion, runoff, low productivity, poor market access |

Habitat fragmentation, loss of biodiversity mining, illegal logging, erosion, overharvesting of rattan, overhunting |

Possible logging, overharvesting of rattan, overhunting |

|

Management opportunities and institutional strategies |

Construc embankments, vegetative stabilization |

Build |

Control fires through firebreaks and fines; suppress Cogon grass |

Control fires, Encourage fruit tree plantation, agroforestry soil and water conservation, suppress Cogon for natural regeneration |

Conservation farming and agroforestry |

Revoke mining lease, revoke logging TLA, assisted natural regeneration, rattan enrichment, local Dumagat forest protectors, use regulations on Wood and NTFPs |

|